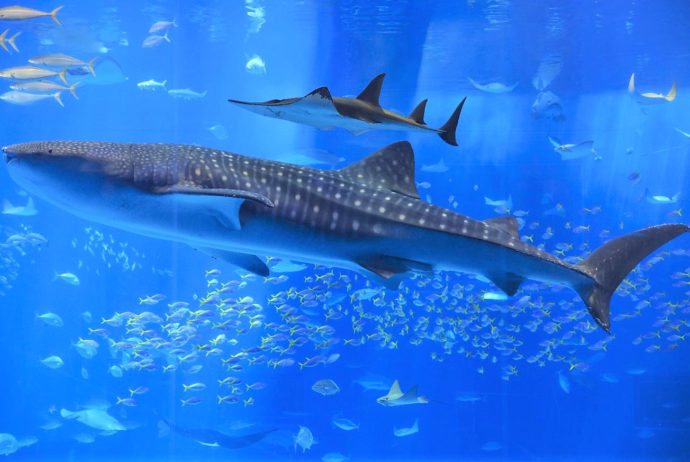

Foraging, starvation and herbivory in the globally threatened whale shark

Whale sharks, filter feeding sharks that travel tropical oceans in search of their microscopic prey, are globally threatened. Despite being the world’s largest fish, reaching over 12 m in length and 21 tonnes, many facets of the whale shark’s life in the open ocean remain unknown. New research based on a collaboration led by researchers at The University of Tokyo’s Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute (AORI) with participants from Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium and the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) published in the journal Ecological Monographs offers new insights into diets, movement and behaviour of whale sharks. The enhanced chemical approach developed suggests that individual specialisation, starvation, and even herbivory may be prevalent in whale sharks. The research is expected to facilitate better understanding and management of this enigmatic species through more detailed assessments of global changes in their feeding and health.

❝Most significantly, we demonstrated how tissue isotopes are strongly connected to rates of growth and feeding…This suggests that it is impossible to accurately interpret chemical signals in the wild without some idea of growth and feeding rates prior to sampling❞

The study used long-term observations of captive whale shark feeding to test chemical approaches for measuring whale shark foraging and health. By combining measurements of different forms (isotopes) of carbon and nitrogen in various tissues, the research revealed a number of important caveats for successfully interpreting these chemical markers in the wild. “Most significantly, we demonstrated how tissue isotopes are strongly connected to rates of growth and feeding” said lead author Dr Alex Wyatt. “This suggests that it is impossible to accurately interpret chemical signals in the wild without some idea of growth and feeding rates prior to sampling”. By correlating growth and feeding with a “health check-up” for sharks based on a blood test, the researchers propose a framework for enhanced chemical investigation of wild foraging. “Similar to blood tests performed when you visit the doctor, we are able to assess the health of these sharks based on a large variety of parameters in their blood and then interpret tissue isotopes in the context of this health check-up”.

A whale shark being fed in Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium

The enhanced approach was applied to wild whale sharks encountered off the coast of Okinawa, Japan, with tissue sampling and a health check-up performed on a number of sharks while freeing them from accidental entanglement in fishing nets. This revealed two distinct foraging strategies in the sharks encountered, identifying individuals that depended or either coastal or open ocean foraging. “By measuring isotopes in a number of tissues with different rates of chemical change, we could demonstrate that these two foraging strategies were consistent across time for the individuals involved, perhaps reflecting individual differences in geographical origins or foraging specialisation over months to years” Dr Wyatt observed. The study made use of a number of advanced tracers, including tissue radiocarbon which showed the sharks fed over a narrow latitudinal range. Dr Wyatt added that “several of the individuals what we encountered appeared to be starving, with blood tests suggesting they may not have eaten for weeks or months prior to sampling”. This could reflect a lack of local prey sources or non-feeding during ocean-basin scale migrations, with the research stressing the need to consider such starvation effects when attempting to chemically identify foraging strategies in this and other poorly understood species.

❝This is a somewhat surprising and controversial finding, since whale sharks are generally assumed to feed strictly on higher trophic levels (zooplankton up to small fish)❞

A whale shark meal composed of two species of krill and some minor amounts of dices fish and fish larvae

Exactly what whale sharks feed on during their time at sea remains somewhat of a mystery. “Despite their enormous size, sustained observations of whale shark feeding remain difficult and rare” says Dr Wyatt. Although open ocean feeding observations are largely impossible, observations at coastal aggregation sites have demonstrated that whale sharks can feed on a range of prey from tiny krill and fish eggs, up to small fish and squid. A new finding in this study suggests that whale sharks may, in fact, be more herbivorous than previously assumed, with tissue amino acid isotopes indicating incorporation of primary producers (plants and algae) into all of the sharks tested. “This is a somewhat surprising and controversial finding, since whale sharks are generally assumed to feed strictly on higher trophic levels (zooplankton up to small fish), although they have been found with seaweed in their stomachs” said Dr Wyatt. In support, recent work published in another study showed that the bonnethead shark, which, like most sharks, is assumed to be strictly carnivorous, can digest seagrass in captivity. “Our chemical estimates of the trophic position of Okinawan whale sharks were consistently low, suggesting that herbivory by whale sharks may be prevalent – this might make sense if feeding opportunities can become as limited as our blood tests suggest” observed Dr Wyatt. Whether herbivory is a consistent strategy, or a response to prey shortages, will be an important aspect of ongoing global work on this mysterious species.

Cartoon Summary. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

The paper, ‘Enhancing insights into foraging specialization in the world’s largest fish using a multi-tissue, multi-isotope approach’ can be found in the journal Ecological Monographs (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1339)